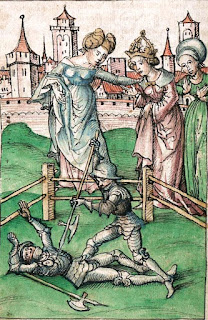

One of the most instructive descriptions of a pollaxe bout

in the literature: Look at the mention of strikes without specifying the part

of the axe used (presumably meaning the mail was used by default), but then the

strike to the fingers, which does,

specifically saying the "sharp of his axe," meaning the taillent; the

mention of striking the "bars of his visor" (meaning they were

wearing grilled visors of the kind many of the LH crowd says didn't exist); the

fact that he struck to the visor with the "handle" (i.e., the queue)

of the axe, just as we're taught to do in Le Jeu; and the fact that he worked

to disarm his opponent, which is one of the most highly favored tactics in Le

Jeu.

CHAPTER XLII.

How they marched one

against the other; each doing valiantly.

And when the Mareschal had given them leave to go, as they

advanced one upon the other, you had thought they had been two lions unchained.

But there was this difference; as Saintré was making for him, he cried aloud,

that all might hear him, “Hah, my ever-gentle dame, and whose I am!” and then

they began to fall upon one another. Then Sir Enguerrant, who was a most

valiant Knight, strong and powerful, and larger built than Saintré, raised his

axe, and dealt him such a blow upon the shoulder that he made him reel, while

Saintré, in return, struck him with the handle of his axe upon the bars of his

vizor, driving him several paces back. Then Sir Enguerrant elevated his axe to

strike a second time; but Saintré, making for him, gave him such a cut over the

hand with the sharp of his axe that neither guard nor anything else could

avail, so that all his fingers were smashed and benumbed. Sir Enguerrant, who

was now hot, nor knew anything of what had happened to his fingers, thought

again to lift his axe, and it was only then he began to feel the pain, and that

he could no longer wield it. So, as a wary and a dauntless Knight, holding his

axe in his left hand, he opened his arms to seize Saintré by the waist. But

when Saintré perceived his aim, he continued to strike, nor ever once let him

approach. And when he saw his moment, all on a sudden he gave him such a blow

on the hand in which he was holding the axe, that he sent it flying in the air;

and when Sir Enguerrant saw that his axe was gone, in sheer desperation he

rushed upon Saintré, to close with him, catching him by one arm. But when the

King saw the axe of Sir Enguerrant upon the ground, and the two together by the

middle, as Prince and Judge sovereign, he at once threw down his wardour, and

said, "Ho, ho!" Then were the two champions separated by the guards.

Then the King, by the Mareschal, called the two champions before him, and then

had said to them, “You, Sir Enguerrant, and you, Jehan de Saintré, the King

desires you should know, that you have each so nobly and so valiantly acquitted

yourselves that it would have been impossible to have done better; but,

according to the articles, the Lord, the King, who here is, has recognized that

the combat was to end either when one or other of you were borne to the ground,

or either had lost his axe from both his hands. So, by the terms, Jehan de

Saintré, the Lord, the King, adjudges to you the prize.”

Vance, Alexander. The

History and Pleasant Chronicle of Little Jehan de Saintré. London: Chapman

and Hall, 1863, pp.128-130.